Multi-State Cellular Automata in WebGL

This is a rewrite and significant expansion of my first cellular automata article. It covers everything in the first article, plus a significant amount of explanation of multi-state automata. If you’re coming from the first article, feel free skip to that part.

I’ve always been fascinated with cellular automata like Conway’s Game of Life. The idea that complex and interesting behavior can emerge from simple rules is captivating to me. In this document I’ll explain my method of encoding a class cellular automata rules, as well as how I implemented my simulator.

The Basics#

Cellular automata are essentially an arrangement of cells with states (in our case, integers) that are determined by a rule. These rules are functions which take the states of a cell and its neighbors as input, and produce the cell’s new state as output. By applying this rule to every cell simultaneously, we advance the simulation in time.

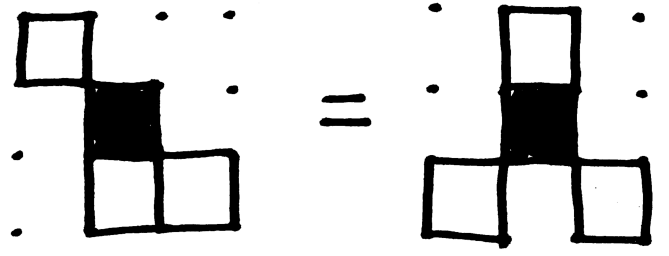

For this undertaking we will only consider totalistic cellular automata with a Moore neighborhood, which contains the eight immediately adjacent cells. By being totalistic, these rules only take into account the total number of cells of each state in the neighborhood, ignoring their arrangement.

With these definitions we can specify a rule function, $F$:

$$ o = F(c, N) $$

$o$ is the output state, $c$ is the current state, and $N$ is a sequence of integers which represents the total neighbor count for each possible state: the $i^{th}$ element of $N$ is the total number of neighbors with state $i$. In the above example, $c=0$ and $N=(3,3,2)$.

To begin, let’s just consider two possible states: “on” ($1$) and “off” ($0$), like in Game of Life. The first thing to notice is that since the total number of neighbors is always 8, we only need to consider the number of ($1$) neighbors, as the number of ($0$) neighbors is always $8 - N_1$. (We could also choose to only count the number of ($0$) neighbors).

So how do we represent the rule function so that we can simulate any two-state rule under our constraints? Well, since the inputs to our functions are just integers, we can use them to index a table, like this one:

| $c$ / $N_1$ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0) | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| (1) | . | . | . | . | . | 0 | . | . | . |

Here, we have a table that contains output states, which we find by querying the table by row (current state, $c$) and column (number of ($1$) neighbors, $N_1$). In the above example, $F(1,5)=0$, so if a cell’s state is ($1$), and it has five ($1$) neighbors, it becomes ($0$).

Let’s try to encode Game of Life in this format. The rules of Game of Life, in English, are:

- Any on cell with two or three on neighbours stays on

- Any off cell with three on neighbours turns on

- All other cells turn off, including cells that are already off

So, in our table representation of $F$:

| $c$ / $N_1$ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Nice and simple! Now we can start thinking about how to use this in a shader. The simulation will take place on an integer-format texture, which we can access like this:

// simulate.frag

#version 300 es

uniform highp usampler2D uSim; // Simulation texture

in vec2 vTextureCoord; // Texture coordinates 0.0 to 1.0

void main(void) {

// Get the current state

int curstate = int(texture(uSim, vTextureCoord).r);

// Determine number of (1) neighbors

int count = -curstate;

for (int x = -1; x <= 1; x += 1) {

for (int y = -1; y <= 1; y += 1) {

if (v == 1) {

count += 1;

}

}

}

}

NOTE: We initialize

countto-curstateto prevent counting the current cell. It also avoids branching, which can be expensive on a GPU, depending on the situation.

Now that we have $c$ as curstate and $N_1$ as count, we can grab our next state from the rule, which is also stored in a texture:

// simulate.frag

#version 300 es

uniform highp usampler2D uRule; // Rule table

uniform highp usampler2D uSim; // Simulation texture

in vec2 vTextureCoord; // Texture coordinates 0.0 to 1.0

out uvec3 fragColor;

void main(void) {

// Get the current state

int curstate = int(texture(uSim, vTextureCoord).r);

// Determine number of (1) neighbors

int count = -curstate;

for (int x = -1; x <= 1; x += 1) {

for (int y = -1; y <= 1; y += 1) {

if (v == 1) {

count += 1;

}

}

}

uint newstate = texelFetch(uRule, ivec2(count, curstate), 0).r;

fragColor = uvec3(newstate);

}

NOTE: Here we use

texelFetch()instead oftexture()to avoid expensive floating-point conversion and fragment-to-texel coordinate conversion. We don’t do this for sampling the simulation texture because it doesn’t support texture wrapping.

To run our simulation, we use two different textures attached to framebuffers, one as output, one as input. By alternating their roles each time step, our desired result is finally produced!

So how many possible rules does this give us? Well, there are 2 possible values for $c$, and 9 possible values for $N_1$ (that’s 0, 1, 2… up to and including 8). Since $F$ can only return 2 possible values, the total number of possible rules is $2^{2\cdot9} = 262144$! Not bad, but we can do better…

Encoding Multiple States#

Although two states is enough to produce interesting behavior, multi-state rules can have some very cool properties, so let’s figure out how to encode these more complex rules efficiently.

First let’s just imagine the case were we have 3 states instead of 2. Not only do we need an additional neighbor count $N_2$ as input to our rule function, but the set of possible inputs becomes more nuanced. For example, if $N_2 = 4$, the possible neighbor counts for ($1$) and ($0$) are restricted, because the sum of all neighbor counts must equal 8. In other words:

$$ \sum^{n-1}_{i=0} N_i = 8 $$

In this case, $N=(3,4,5)$ is invalid because the sum of $N$ would unfortunately be 12, not 8. Of course, this applied our 2-state case as well, but we didn’t have to worry about it because the value of $N_0$ was implicitly defined solely by $N_1$.

So how do we index our rule texture with this property in mind? Well, let’s start by looking at how we might want to map possible $N$s to indices, by sort of “counting up”:

| input states ($N_0$,$N_1$,$N_2$) | index |

|---|---|

(0,0,8) |

0 |

(0,1,7) |

1 |

(0,2,6) |

2 |

| … | |

(0,7,1) |

7 |

(0,8,0) |

8 |

(1,0,7) |

9 |

| … | |

(1,6,1) |

15 |

(1,7,0) |

16 |

(2,0,6) |

17 |

NOTE: We are just considering $N$ here because adding in $c$ is simple: we just multiply the index of $N$ by $c$ to get the final index into the rule texture.

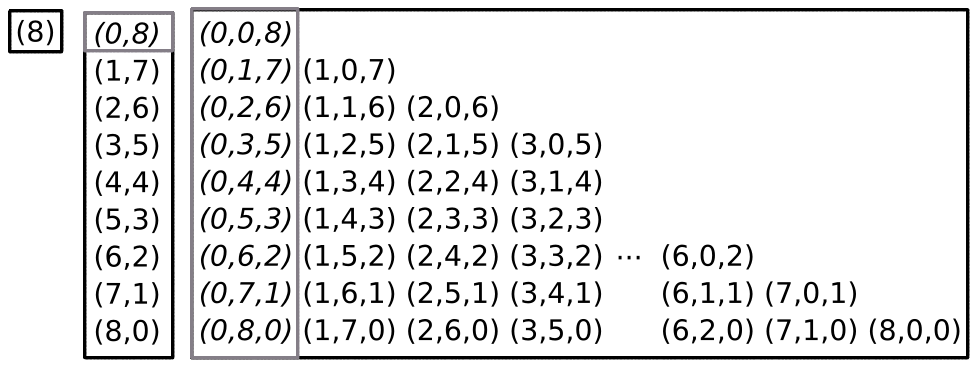

The first thing to notice is that the first 9 entries have $N_0=0$, which is like we only have two states. This means that if we allowed for a 4th state, we could just add on to the end of the table. It also means we can express the length of the table (the total number of possible $N$s) as a function of the number of states, $n$.

One state has 1 possible inputs, two states has 9, and if we extended the table we’d find that 3 states gives us 45 possible inputs. The OEIS tells us that the sequence of 1, 9, 45, … is $\binom{n+7}{8}$. Notice: 8 is our target sum and 7 is just 8-1. Indeed, $\binom{n+s-1}{s}$ is the general form for any target sum $s$.

So where do these numbers come from? Well, if we arrange the possible input sequences by state, it becomes clear:

Now that we can compute the maximum index of any sequence given its length $n$, and target sum $s$, we can finally compute an index. The process is this:

$$ \text{for } i=0 \text{ to } n-1:\ v = v + \binom{s + n - i - 1}{s} - \binom{s - S_i + n - i - 1}{s - S_i} , s = s - S_i $$

…where $v$, which is initialized to 0, is the computed index of the given sequence $S$. $s$ is the remaining sum of the elements in the sequence after $i$, which begins as our target sum (for our purposes, 8). $s$ decreases by the value of each element of $S$ as we iterate through it.

$\binom{s + n - i - 1}{s}$ is the formula for computing max index, except we are computing the max index for the sequences of length $n-i$ which sum to the remaining sum of the whole sequence, $s$.

$\binom{s - S_i + n - i - 1}{s - S_i}$ provides the max index of the sequences of length $n-i$ which sum to $s-S_i$, which is just the remaining sum after the element $S_i$.

Taking the difference of these two quantities gives us the index of the sequence up to $i$. By summing all $i < n-1$, we get the index of the whole sequence!

For clarity, I’ve also written the algorithm in Python:

# n: sequence length

# S: the sequence

# s: the integer value which each sequence sums to

# The computed index, starts at 0

v = 0

# algorithm: Consider each element of the sequence S as a subsequence,

# where each element is an increasingly smaller subsequence.

# By summing together the indices of each subsequence, we get the

# index of the whole sequence. We start with the longest subsequence.

for i in range(n - 1):

# l: Max index of subsequence that sums to n minus whatever we've seen so far

l = comb((s) + (n - i - 1), s)

# r: Like l, but for sequences that sum to current minus S[i], the element we are considering

r = comb((s - S[i]) + (n - i - 1), s - S[i])

# Add l-r, the index of the part of the sequence we've seen so far

v += ( l - r )

# Subtract the current sequence element from current sum

s -= S[i]

Implementation#

To implement this algorithm efficiently in a shader, we need to pre-compute binomial coefficients into a texture:

function buildBinomial() {

const data = new Uint32Array(32 * 32);

data.fill(0);

for (let n = 0; n < 32; n++) {

for (let k = 0; k < 32; k++) {

data[k * 32 + n] = binomial(n, k);

}

}

const binomialTex = this.gl.createTexture();

this.gl.bindTexture(this.gl.TEXTURE_2D, binomialTex);

// We use 32-bit unsigned integers because we need to store large numbers

this.gl.texImage2D(this.gl.TEXTURE_2D, 0, this.gl.R32UI, 32, 32, 0, this.gl.RED_INTEGER, this.gl.UNSIGNED_INT, data);

}

We access the texture like this, using texelFetch():

#version 300 es

uniform highp usampler2D uBinomial

// Returns binomial coefficient (n choose k) from precompute texture

int binomial(int n, int k) {

return int(texelFetch(uBinomial, ivec2(n, k), 0).r);

}

Finally, we have everything we need for the final shader!

// simulate.frag

#version 300 es

precision mediump float;

uniform highp usampler2D uSim; // Input states texture

uniform highp usampler2D uRule; // The cellular automata rule

uniform highp usampler2D uBinomial; // Precomputed binomial coefficents

uniform vec2 uSize; // Size of simulation canvas in pixels

uniform int uStates; // Number of states in this rule (MAX 14)

uniform int uSubIndices; // Number pf subrule indices

in vec2 vTextureCoord;

out uvec3 fragColor;

// Returns binomial coefficient (n choose k) from precompute texture

int binomial(int n, int k) {

return int(texelFetch(uBinomial, ivec2(n, k), 0).r);

}

void main(void) {

int curstate = int(texture(uSim, vTextureCoord).r);

// Neighbor counts by state index

int N[14] = int[](0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0);

N[curstate] = -1;

// Determine neighbor counts

for (int x = -1; x <= 1; x += 1) {

for (int y = -1; y <= 1; y += 1) {

uint i = texture(uSim, vTextureCoord + (vec2(x, y) / uSize)).r;

N[i] += 1;

}

}

// Determine the index of the integer sequence formed by the neighbor counts

int seqIndex = 0;

int s = 8;

for (int i = 0; i < 13; i++) {

if (N[i] > 0) {

int x = uStates - i - 1;

seqIndex += binomial(s + x, s) - binomial(s - N[i] + x, s - N[i]);

s -= N[i];

}

}

// Compute final index into rule tex given current state and neighbor states

int ruleIndex = curstate * uSubIndices + seqIndex;

// Convert 1D rule index into 2D coordinate into rule texture

uint newstate = texelFetch(uRule, ivec2(ruleIndex % 1024, ruleIndex / 1024), 0).r;

fragColor = uvec3(newstate);

}

Now we have a working shader that simulates arbitrary multi-state cellular automatons! You can see a live demo here, and all the source code here.